This article originally appeared in the 2020 issue of Rice Engineering Magazine.

When their labs on campus shut down in March, Caleb Kemere and Jacob Robinson wanted a way to use their skills to protect medical workers on the COVID-19 front lines.

After consulting with Dr. Sahil Kapur, a plastic surgeon at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, Robinson and Kemere realized something often misunderstood by the public: N95 masks use essentially the same filtration method as more readily available surgical masks.

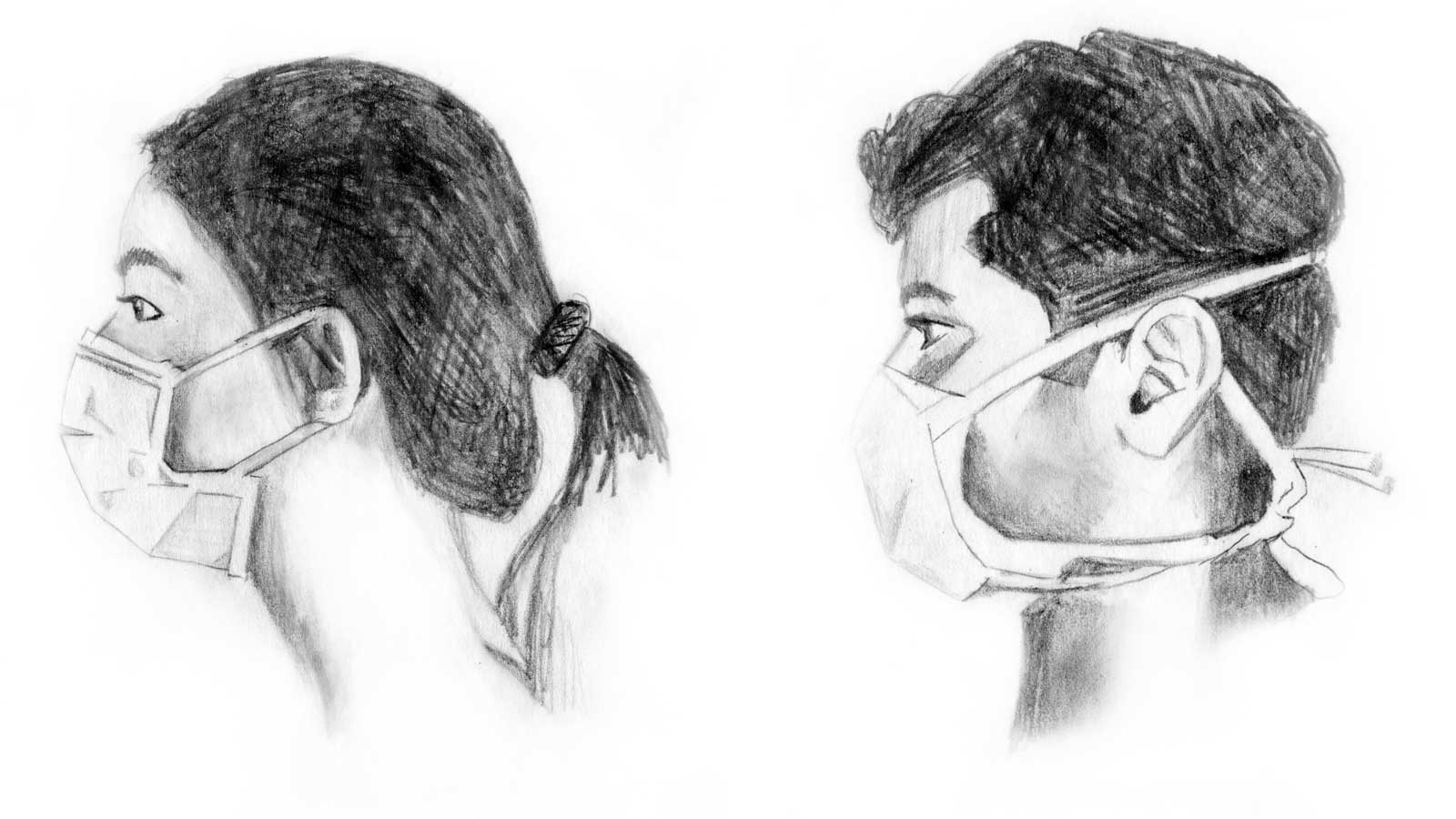

“The N95 masks are more effective mainly because they are custom-fitted to an individual’s face. The mask forms a seal around the mouth and nose so when you breathe in and breathe out, you’re forcing all air to go through the filtration material,” Robinson said. “Surgical masks aren’t fitted, so if you could find a way to make them seal around your face, they might provide similar protection.”

Kemere and Robinson are both associate professors of electrical and computer engineering, and assistant professors of bioengineering at Rice.

This realization sparked the rubber-harness project that Kemere, Robinson and Kapur are prototyping and testing. Made from a single piece of inexpensive silicone rubber, the harness could potentially solve the scarcity of personal protective equipment. Collaborating with the organization Fix the Mask, the team hopes to manufacture the harnesses and give them free-of-charge to medical professionals.

The harnesses are reusable. Rubber, unlike disposable mask material, can be readily sanitized – but the harnesses need to be thoroughly tested before any mass-production occurs. That’s where the Rice COVID-19 research funding comes in.

“There’s a fancy machine,” Kemere said, “that measures the difference in small particles between the exterior and interior of the mask. It’s called a PortaCount, and thanks to this grant we have purchased one for use at Rice.”

Kemere, Robinson and Kapur have broadened the scope of the project beyond Houston and even the United States. Their plans could eventually provide free harnesses to medical professionals in the developing world.

“We were thinking about solutions that could be mass-produced at a low cost,” Robinson said. “A single piece of silicone material that we can make for a dollar or less can be donated. If we receive $10,000 from a donor, we can give 10,000 harnesses to people who could use them.”

For now, thanks to support from the research fund, the team will continue testing the harnesses and share their findings.

“One of our big goals in terms of actually doing proper measurements and a proper study is that the next time this comes around, somebody sees that people from Rice back in 2020 figured out that you could just stamp a ring out of rubber to fit over a mask,” Kemere said.

“We are hoping to contribute to this literature. Being an academic, the papers you publish don’t usually have that sort of value. But I think in this case, there really is value in documenting everything we are doing with an eye to helping future healthcare providers and leaders.”